“[The Virgin Islands], in brief, has not been an isolated and inward-turned community slowly and imperceptibly building up a powerful sense of meaningful communality on the twin pillars of stability and continuity, but rather an outward-confronting, tropical state of nature successively shaken by the rude, elemental force of invading immigrant peoples bound together, at best, by fragile and tenuous relationships.”

– Gordon K. Lewis, The Virgin Islands: A Caribbean Lilliput, (1972).

The problem of colonial education is a well-worn issue in Caribbean social criticism. Every major Caribbean thinker has had something to say about pedagogy. Frantz Fanon’s exasperation is memorable when he noted that school children in his native Martinique were learning their history from books that began with the words, “Our ancestors the Gauls…”, the problem being that the majority of “ancestors” to Martinican people were not Gauls at all.

And it is not just education in the Caribbean that may have damaging effects on local students. It is also the education that Caribbean people receive abroad. One of my favorite passages from George Lamming’s The Pleasures of Exile argues that British Caribbeans should not attend University in England:

“…Not because England is a bad place for studying, but because the students whole development as a person is thwarted by the memory, the accumulated stuff of childhood and adolescence which has been maintained and fertilized by England’s historic ties with the West Indies. It would have been better, perhaps, if he had gone to study in France or Germany, to mention countries with a different language; any place where his adjustments would have to take the form of understanding the inhabitants from scratch.”

I can’t help but think of this when I see school children walking around my home island of St. John carrying worn and outdated copies of textbooks entitled These United States. I couldn’t help but be reminded of it last year when I substituted for an elementary school class and was left a lesson plan to teach the students that autumn arrives with the changing of the leaves. This is I think what Édouard Glissant means when he refers to societies that “little by little get lost in the unreal, and so irresponsible, use of language.”

Addressing these issues requires consensus, and that is something that Caribbean societies — including my own — are not known for. In the U.S. Virgin Islands, where immigration has been emphatic and forceful, the present can seem under-determined. In America’s Virgin Islands: A History of Human Rights and Wrongs, historian William Boyer writes:

“No other locale in the Caribbean […] or elsewhere in the world for that matter – had undergone such radical and rapid ethnic and economic change in the 1960′s than that experienced by America’s Virgin Islands.”‘

If our present isn’t neat, pure, or singular, the urge is to go looking for those qualities in the past. But since the past is often just a projection of our current anxieties and desires, our dilemma is never resolved. Yes, the pluralism that is often said to be an admirable quality of Caribbean islands is a gift; but it can also be experienced as a lack when we are feeling frustrated and cynical.

During the “development decade”, the era beginning in the early 1960s, the modern USVI economy was born, and along with it the demand for labor that would be met primarily by men and women from other Caribbean Islands. Thanks to the booming economy, more people from the mainland United States also chose to make the Virgin Islands their home during this period. Suddenly three major contradictory narratives existed side by side each other in the territory. Some Virgin Islanders had become Americans by the purchase of their home. Some had become Americans by choice, seeking economic opportunity in the USVI. And for some, habitation in the Virgin Islands was a half-hearted escape from America without the disruptions of a forfeited citizenship. These narratives — each saying something about our relationship to the United States — do not seem to be reconcilable

Those of us who grew up in the Virgin Islands from the 1960s onward are the heirs to the aspirations and degradations of the development decade, its successes and its failures. So why is this recent past so often invisible to us? The fluctuating world in which we were born has the illusion of permanence. But the development decade was nothing if not an abrupt rift in the past separating forever two eras, the time before and the time after.

Within the shifting realities of the U.S. Virgin Islands, the youth are the wildcard. Their memories are still fresh and untainted by nostalgia. They have no world but the one that is in the process of being born. How can educators in the Virgin Islands, responsible for helping the young develop, understand the nuances of the new world that their students belong to?

In 1983, Commissioner of Education and future Governor of the U.S. Virgin Islands Dr. Charles W. Turnbull contributed an article to Volume I, No. 8 of VI Education Review, entitled “Migration and Educational Disequilibrium.” In it he charts the challenges faced by the Virgin Islands education system in the wake of the development decade. He puts some things in clear perspective. Here are the astonishing numbers:

“In the period 1960 – 1975 the population of the U.S. Virgin Islands almost tripled, increasing by 188 percent [!!!]. The fastest growing state in the United States in the same period was Nevada whose population increased by 103 percent. It should be noted that the change in population per square mile on St. Thomas increased from 506 in 1960 to 1,372 in 1975. This placed St. Thomas second only to Barbados in the Caribbean and higher by far than any state in the Union.”

The children of non-citizen residents were at first excluded from the USVI public school system on the basis that the schools were already overburdened, but when the courts ruled that all children be given access to public education, the Virgin Islands public school district became one of the largest under the U.S. flag (188th out of 11,000 districts by the late 1970s). Dr. Turnbull notes that public school enrollment in the USVI in 1968 was 11,497 students. By 1981 it was 25,585 students.

And the educators? Many teachers, too, during this period were recent arrivals to the U.S. Virgin Islands. Turnbull writes:

“Particularly challenging and critical was the dilemma of the many non-Virgin Islands and non-West Indian teachers, most from the continental United States…who faced the awesome task of assimilating the immigrant child into a new and different school system. Very little in their background and training had prepared them for this. Not to be forgotten was the fact that the continental teachers faced assimilation problems themselves in some ways, not unlike the very immigrant children they were recruited to serve.”

I think this is Turnbull’s very polite way of saying that many well-intentioned people may have in fact only added to the confusion of young Virgin Islanders of the late-20th century.

Such an enormous increase in enrollment would naturally put strains on any school system, but this was an influx of students into schools which already, according to Dr. Turnbull’s article, “routinely held thirty, forty, and even fifty children per class.” Virgin Islanders made great sacrifices in this era, but sometimes the challenges were daunting enough to create strains within the community, or as Turnbull writes of the conflict over limited public education resources:

“Manifestations of this conflict were vividly evident at P.T.A meetings, school registrations and on radio talk shows. This had the effect of straining the chords of unity and tolerance in the multiracial, multicultural Virgin Islands.”

This sort of conflict, born of mass-immigration, is not at all unique to the USVI. The Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes wrote of the hypocrisies of our age that, “We celebrate the so-called globalization process because it facilitates the movement of goods, services, and securities around the world in a truly extraordinary manner. Things are free to circulate. But workers, human beings, are not.”

The equation, everywhere in the world, even in very generous communities (which I believe the U.S. Virgin Islands to be), is that an overcrowding of the commons creates conflict. This is only interesting insofar as these conflicts shape societies, and that they also can produce the conditions for healing.

More than these conflicts, I am interested in the idea of education itself, and what it means to a culturally-diverse community. Do educators have some obligation to put us all on the same page? What about the erasure of difference that this entails? I think this is where the idiosyncratic USVI dynamic I have just described may resonate beyond our shores. What path should schools take when faced with an influx of students (and teachers!) labeled by society as “alien” or foreign? Isn’t the language surrounding assimilation a bit frightening? But at the same time, raising a generation of outsiders also seems problematic. Today all teachers in the USVI are required to take a course in local history, but is that enough? Dr. Turnbull makes his opinion on the role of education clear at the end of the article when he writes:

“..as a result of institutional stress, the role of the school as transmitter of traditional social values became blurred and defused.”

I did not attend public school in the USVI. Others must speak to that experience. I was a student at private schools on both St. John and St. Thomas, and as a result of this, I can count on the fingers of one hand the number of teachers I had who even identified as Virgin Islanders. Many would say this shouldn’t matter. In part, I agree. All human hearts have the same capacity for understanding others. Falling into a myopic nationalism is useless, even when we are faced with confusing times.

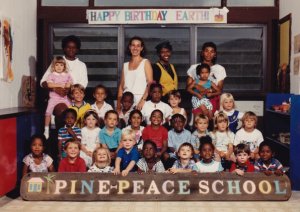

But there is another side to this story as well. What do private school students in the U.S. Virgin Islands lose by being educated in what are essentially mainland-oriented institutions? Does it matter that many of these students come from families who have arrived in the Virgin Islands relatively recently? If they choose to integrate into the mosaic that is the Caribbean – their home – they will not learn how to do so at school.

Following this line of thought can lead to distressing comparisons to an era in the Caribbean that we like to believe is over. There is a long tradition in the region of education serving the sinister – at least, to local people – purpose of creating good British, French, Spanish, Danish and Dutch citizens.

Shouldn’t local knowledge be given precedence in our schools over classes in U.S. Civics and U.S. History? Shouldn’t all children raised in the USVI be given the knowledge to place themselves in the context of their society, and indeed, the broader world? A very wise man once said that “national consciousness, which is not the same as nationalism, is the only thing that can give us an international dimension.”

One of the legacies of the USVI’s development decade is an education system that has frequently given young Virgin Islanders a conflicted sense of national consciousness. As for those educators who do their best to instill in their students the sort of generous global sensibility that can only come from a strong pride in place, I can only hope they know what a difference they make.